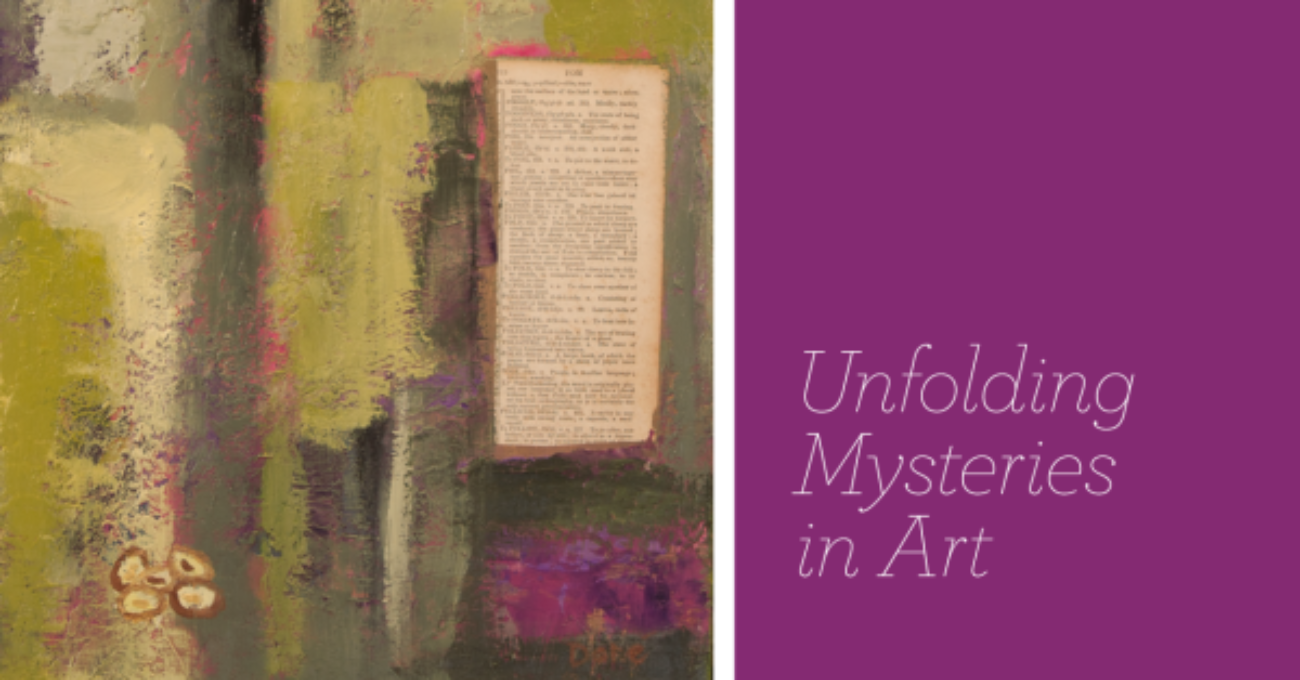

Unfolding Mysteries in Art

El Paso Artist Rhonda Doré often props a blank canvas against a set of drawers near her easel.

As she works on one piece of art, applying layer after layer, she’ll dash streaks of paint onto the blank canvas below.

“I hate a white canvas,” Doré said. “The first thing I do is just cover it with something—anything. I mean, I’ll grab any random color, just to cover that white—it’s so accusatory.”

For Doré, the blank white page is like a mystery—daunting to behold, yet full of potential. It’s not until she begins covering the canvas that she begins uncovering the mystery of what the work could someday become.

“It’s like stepping into the void, every single time,” Doré said of creating abstract art. “Sometimes things come to you while you’re working, and you don’t even know where they came from. It’s amazing to watch the unfolding of it.”

Doré’s work is slated for an exhibit March 11 at Art Avenue Gallery, 1618 Texas St. Suite E. Titled Above & Below, the exhibit features artworks from two of Doré´s recent series: The Archaeology of Memory and Where Things Bloom.

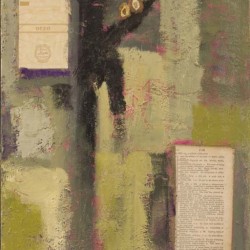

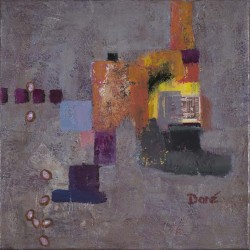

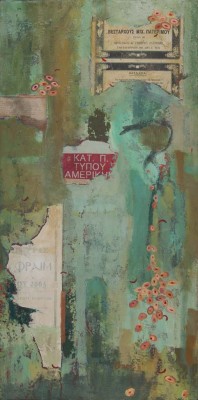

Doré’s abstract paintings, built in layers, rich in color and texture, often contain hints to hidden mysteries—stories that tell of the passage of time and of “the small, meaningful occurrences in our lives,” according to her artist’s statement.

Doré is vice president and group creative director at Sanders/Wingo, an El Paso advertising agency.

About 15 years ago, one of Doré’s clients invited her to a continuing education art class at UTEP.

“The first day, they gave us the primary colors on a paper plate, and I mixed mud,” she said. “I mean, everything was just brown. I had no clue what to do.”

But Doré stuck with it. Eventually, she discovered she had a fondness—and a talent—for abstract painting. She began exploring art theory, listening to podcasts about artists and searching for methods she could adapt into her work. Despite her full-time position at the advertising agency, she carved out time to paint. And her desire to master the craft fed into her passion for it.

“The more that you do of anything, the better you become,” Doré said. “And there’s a reason for that. You learn things other people can’t teach you. If you want to draw a picture of a bird, you better draw 50 pictures of a bird. And pretty soon, you’re going to go, ‘Look, I can draw a picture of a bird.’”

Las Cruces resident Ron Fritsch, who retired in December from Sanders/Wingo, said he’s followed Doré’s work and process for about a decade.

“She’s had tremendous growth in her work,” said Fritsch, who’s also an artist. “It has a spontaneous look to it. It’s very carefree, but, at the same time, precise.”

Doré’s works contain scraps of paper surrounded by layers of textured paint. She collects these papers from places so wide and varied as to defy categorization: garage sales, alleyways, junk stores, foreign countries and more.

“Everybody has papers attached to their lives,” Doré said. “They help tell your story. Whether you like it or not, you’ve got a birth certificate, you have a driver’s license, a courthouse record. Everybody has something…And, to me, those kinds of papers are the fascinating ones.”

Part of that fascination stems from each paper’s mysterious history, Doré said. For example, she once bought a box of papers that belonged to a Kansas farmer named Harold Nelson. She included one of Nelson’s old checks in a painting that would later be exhibited at the El Paso Museum of Art.

“As I worked on the painting, I found myself thinking about Mr. Nelson every once in a while,” Doré said. “I wondered, ‘What was he like? Who was he?’”

She later did some detective work and found an online listing for Nelson’s headstone in a church graveyard.

Before presenting the piece, Doré made a press release, and, on a whim, sent it to newspapers near the Kansas town where Nelson had lived. She hoped to find someone who knew him—someone who might find it interesting that one of Nelson’s old checks “would be hanging on the wall of a museum. ”

To Doré’s delight, an editor rang her on the phone.

“He said, ‘Harold Nelson was my very best friend,’” she recalled.

Doré and the editor had a long chat. She learned that after Nelson died, his adopted children organized an estate sale. The newspaper editor attended the sale. He tried to buy as many of Nelson’s personal items as possible, so as to keep them from scattering, but he evidently “missed this box,” as Doré put it.

Before hanging up, Doré agreed to send the box of papers to the editor. In return, the editor sent her a photograph of Nelson.

“For me, it was proof that every little thing has a story,” Doré said. “You may not know the story, but it’s got one. And that’s a wonderful mystery to explore.”